To say I am a goal-oriented guy is putting it mildly. Some might say I’m a goal-setting fanatic, and maybe they’re right. I have been setting goals to achieve my dreams for as long as I can remember. In fact, I have a file with all my annual goals from 1990 to today, and I keep my current year goals tacked up on a wall. While I may be inching my way to the fanatical end of goal setting, the truth is, we are all wired to set and achieve goals from a young age.

When we shake a rattle in front of an infant and then stop its rattling, what does the infant do? They attempt to reach for the rattle with the goal of recreating the sound it just made. When an infant crawls across the room, it is generally with intent to reach an object or person. They are directing effort towards the end result—the very definition of “goal”—they are hoping to achieve. Our understanding of goal-directed action that results in a successful outcome is developed as early as eight months. By 12 months, we’ve developed an understanding of goal-directed actions that result in an unsuccessful outcome—we learn what won’t get us what we want. We come to these understandings of goal-directed activities through our own attempts and by watching the attempts of others.

The steps involved in goal-directed activity, namely motivation, goal seeking, successful outcome, and feelings of pleasure, are wired into the brain’s structure.

If we’re hardwired to pursue goals, why does it sometimes feel so hard to achieve them?

In his article, The Neuroscience of Goals and Behavior Change, Elliot T. Berkman explains the balance required between the following two axes to change our behaviors in order to reach our goals:

- Level of skill, knowledge, or ability required by an action.

- Level of motivation required by an action.

Before we see what that looks like, it’s important to understand that our brain has evolved to learn through rewards which motivate us to work hard to recreate the task/activity. Rewards can help us reach our goals, right? Yes, they can, but establishing a new behavior to help us reach our goals is difficult because we have yet to be rewarded for it, so we fall back on the behavior that has been consistently rewarding us.

Losing weight is a goal most of us can relate to. Let’s say you want to lose 20 pounds. To do that, you decide to start exercising every day. The only time you have to exercise is in the morning before you go to work, so you decide to get up an hour earlier to go to the gym. The first day you get up and go. The workout doesn’t feel good, you’re sweaty and out of breath and you’re tired because you lost an hour of sleep. You don’t see the reward.

Day two you get up and go even though it’s cold and rainy. Day two your workout doesn’t feel good—you’re still sweaty, out of breath, tired, and cold and wet. You don’t see the reward.

Day three the alarm goes off, and your brain decides the behavior with the familiar reward is the path you’ll take this morning (yup, we’re also wired to take the path of least resistance). You shut off the alarm, close your eyes and you’re rewarded with an extra hour of sleep.

Achieving goals most often requires us to change our behavior, and according to Berkman, “Attempting to change behavior in a systematic way by engaging in new behaviors which have never been reinforced often means working against this powerful system.”

Sounds like we are set up for failure before we even get started—but that’s not an excuse to stop trying. Instead, this understanding is an opportunity to find ways to fight our natural tendencies toward familiar rewards and the path of least resistance, so that we can convince our brain that we do in fact want to change our behavior.

Let’s look at intentional ways in which we can do that.

Berkman’s axes of level of skill, knowledge, or ability and level of motivation that are required to change behavior are broken down into the following four categories:

- Simple and Routine Tasks requiring low skill and low motivation – pouring glass of milk

- Simple but novel tasks requiring low skill and high motivation – cleaning a toilet for the first time

- Complex but routine tasks requiring high skill and low motivation – driving to the house of a friend who lives in a familiar area

- Complex but novel tasks requiring high skill and high motivation – driving on a highway for the first time

The level of effort required to obtain the necessary skill, knowledge, or ability must work in tandem with the level of effort required to obtain and maintain the necessary level of motivation to change behavior. For our purposes today, I want to focus on motivation.

Try categorizing the behaviors you want to change to reach your goals to help. For example:

You recently learned that acquiring a specific certificate in your field will accelerate the promotion you want. This would fall under Complex but Novel tasks: you need to both learn new, complex knowledge and have high motivation to do so. In this case, the chance for promotion provides the high motivation fuel you’ll need. One of the primary lessons Berkman draws on is that the greater we connect our brain’s motivation/reward system with parts of our brain connected to self and identity, the more likely we are to successfully reach our goals. Our sense of self and identity is composed of our memories, values, beliefs, and relationships.

If we take away the built-in motivator from the above example, what would that look like? You’re required to complete the certificate program, not only is it not of real interest to you and will not result in a promotion, but it’s a goal placed on you by someone else. Still a complex but novel task, but it will require greater effort on your part to connect your brain’s motivation system to the task at hand. With the power of this information, how might you build in rewards to keep you on track with the goal of completing the certificate program and feel good about it? How can you connect it to your values, beliefs, memories: your sense of self?

Be purposeful in this exercise. You’ll find tips to get you started on connecting your feelings to your goals here.

So now we know that we are intrinsically wired for motivation, goal seeking, successful outcomes, and feelings of pleasure—all goal-oriented tasks—and that we are best motivated by reward (both tangible and intangible) and goals that we can connect to our sense of self (values, beliefs, memories).

Along with that knowledge, we’ve added the tool of categorizing the level of skills, knowledge, or ability required to reach a goal alongside the level of motivation required. Incorporating that tool into your goal-setting steps will give you greater power to create rewards that are meaningful to you, which in turn will increase your motivation.

Through science, we also understand that goal-directed behavior requires us to focus our attention on relevant information (selective attention) and ignore distractors (interference suppression). This can be challenging in a world filled with more distractions than we could have imagined 30 years ago. This onslaught of distraction has decreased our selective attention span to 40 seconds on average when working in front of a computer.

Here again, knowledge is power. Pay attention to how easily you are distracted along your path to your goals and what those distractions are. Which ones can you eliminate all together? Is that YouTube video you just got sucked into relevant to the task at hand? For the essential life distractions that we sometimes use as an excuse to stop working on our goal (maybe I should throw in a load of laundry), how can you better block out time for those essentials without interrupting the time allotted to focus on your goal? For more ways to increase your mental focus and tame distractions, go to Things You Can Do to Improve Your Focus and Strategies for Overcoming Distractions.

Here’s yet another proven method we can incorporate into our goal-reaching journey to increase our chances of success:

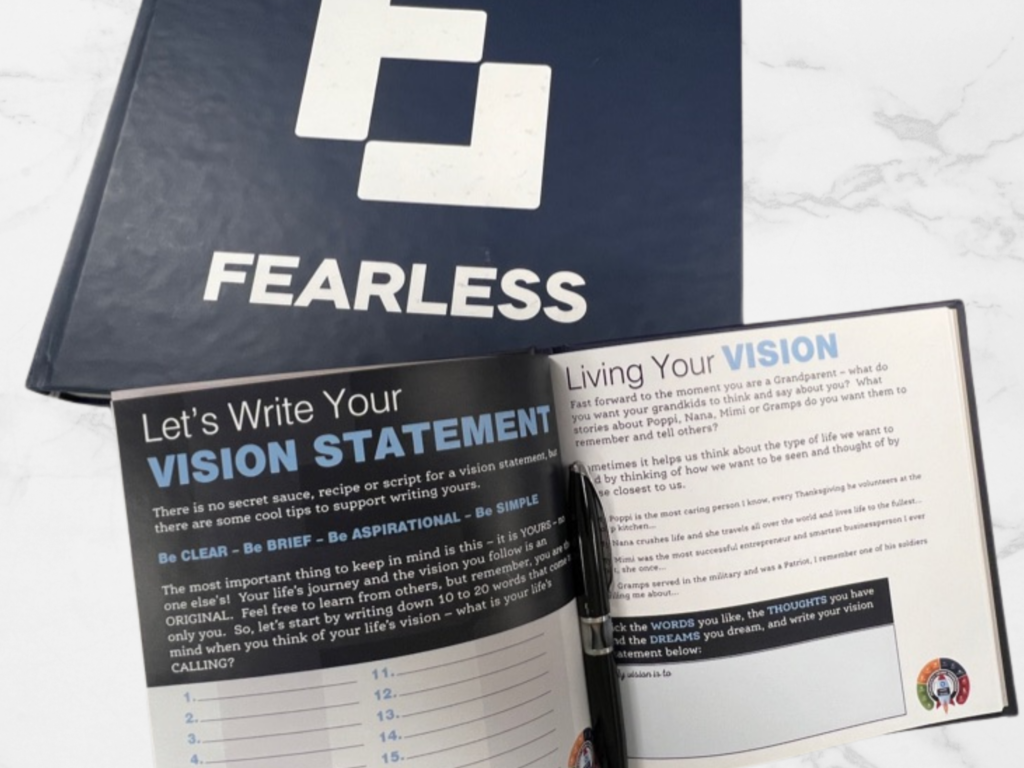

Put your goals on paper

Studies show that by writing your goals down daily, you are 42 percent more likely to achieve them.

But don’t stop there. Write a brief description of each goal and identify two to four actions you can take to support that goal. Prioritize those actions based on short-term vs long-term and urgent vs important—and equally important setup rewards along the way that help you stay connected to your goals.

So, the next time your brain tries to convince you to turn off the alarm and pull up the covers, remember you have the power to retrain your brain to be rewarded by the benefits of going to the gym and staying in shape: you feel better, have more energy, and with all that dopamine you’ll be pumping in, you will also have increased motivation to set new and bigger goals.